And They Lived Unhappily Ever After: The Anti-Fairy Tale

Introduction

In one of the most well-known high fantasy adventure novels of all time, The Lord of the Rings by John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, The Lady Galadriel says about the Ring passing out of knowledge that ‘History (of it) became legend, legend became myth.’ We give legend and myth oral and written form as folk tales and, thanks to the seventeenth-century French writer, Countess d’Aulnoy, the fairy tale, or conte de fées, was first named and used as a literary device. However, as the body of fairy tales grew, a new story form was named, that of the anti-fairy tale, providing tragic rather than happy endings, victorious antagonists, and defeated protagonists. With the anti-fairy tale showing no sign of losing its postmodern appeal, this essay asks whether the anti-fairy tale is superior to the traditional archetype fairy tale, by focusing on the European tale Little Red Riding Hood.

Birth of the fairy tale

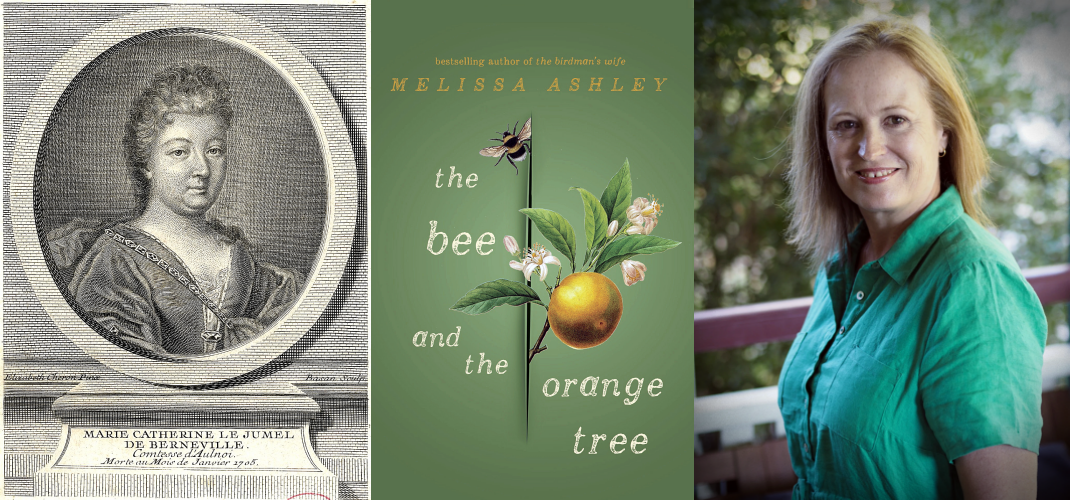

Before discussing the anti-fairy tale as a concept, it is necessary to give some background information about the creation of the fairy tale itself, as the former could not exist without the latter. In her historical fiction novel, The Bee and the Orange Tree published in 2019 and given coverage in the Guardian online that same year, the Australian author Melissa Ashley themes her narrative on the exploits of Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville d’Aulnoy (Countess d’Aulnoy). The publisher’s blurb for Ashley’s novel succinctly mirrors the oppressive and often dangerous conditions Countess d’Aulnoy and women of her time had to endure stating:

It is 1699, and the salons of Paris are bursting with the creative energy of fierce, independent-minded women. But outside those doors, the patriarchal forces of Louis XIV and the Catholic Church are moving to curb their freedoms. In this battle for equality, Baroness Marie Catherine d’Aulnoy invents a powerful weapon: ‘fairy tales.’

Ashley’s novel is named after Countess d’Aulnoy’s French literary fairy tale of the same name (in French, L'Orangier et l'Abeille), produced in the latter’s Tales of Fairies (Les Contes des Fées). Before the fairy tale writings of the Brothers Grimm in Germany and Hans Christian Andersen in Scandinavia, d’Aulnoy and her peers (a coterie of French female writers known as the conteuses, or storytellers) were creating their novella-length, intricate (and often far-fetched) fairy tales and reciting them in fashionable French literary salons. By using embroidered narrative, parody and integrating motifs and tropes from myth and folklore, codes of medieval valour and the works of earlier feminist French writers, the conteuses fought back against an increasingly authoritarian and repressive androcentric society that endorsed arranged marriages and undermined the freedom and choices of women at every turn.

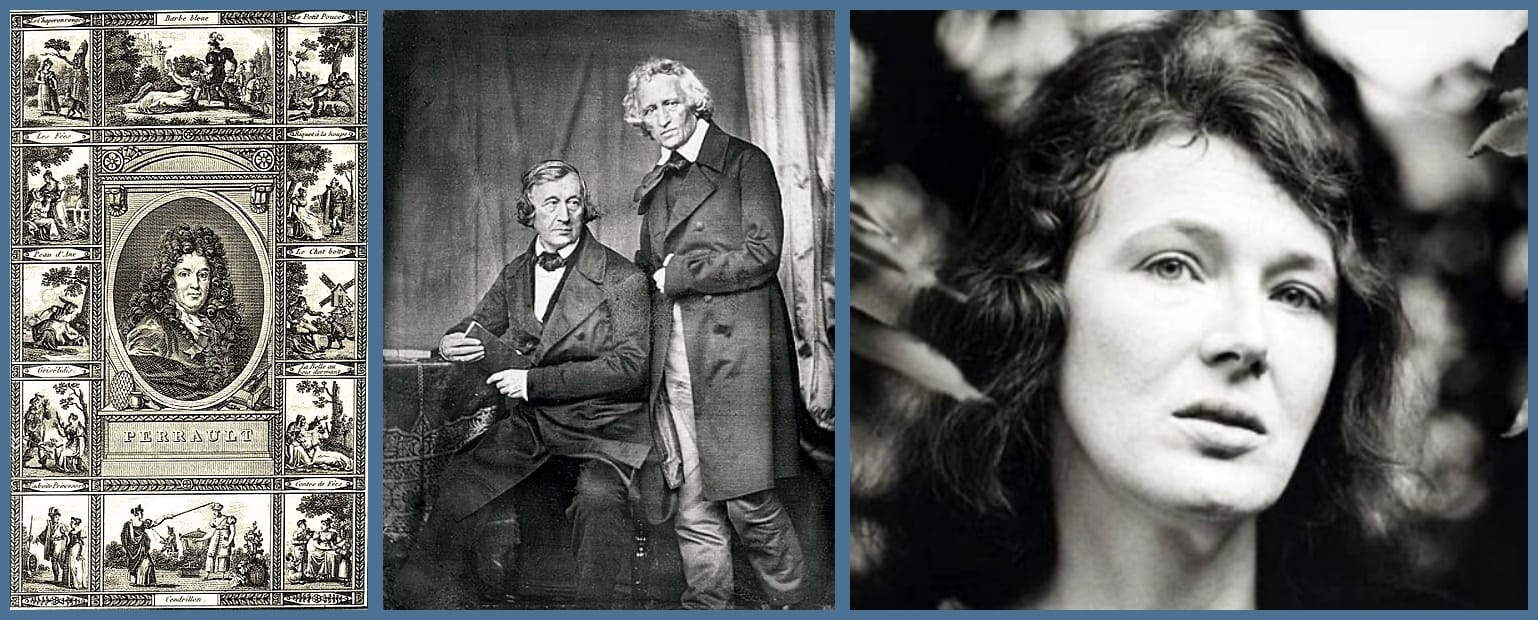

Ashley notes that, in the 19th century, when the Brothers Grimm started collecting and publishing their own folktales, they rejected the fairy tale writings of the conteuses as false and unrepresentative of the voice of the common people, or volk. In dismissing the work of Countess d’Aulnoy and her fellow conteuses, one could state that the masculine stance of the Brothers Grimm and others like them gave rise to the earliest example of anti-fairy-tale-like behaviour, although the term itself (German: Antimärchen) was not used until 1929/30 by André Jolles, a Dutch-German art historian, literary critic and linguist, in his literary work Einfache Formen (Simple Forms). With time, and because of the unrelenting assault on their only female coterie of storytellers, the fairy tales of the conteuses eventually fell from fashion in the 18th century; however, not before they had created the archetypes of many of the fairy tale heroines we know of today.

Fairy tales reformed: little red and the anti-fairy tale

It was in 1695 that Charles Perrault, the French author, gave the world his rendition of a folk tale that had already appeared in several European (and other) countries about a female child and a wolf. His tale Le Petit Chaperon Rouge (Little Red Riding Hood), formed part of his 1697 edition of Histoires ou contes du temps passé, subtitled Tales of Mother Goose (Les Contes de ma Mère l'Oye), an edition that included The Sleeping Beauty, Puss in Boots, and Cinderella. Perrault wrote Little Red Riding Hood to caution his readers about predatory men accosting and apprehending young girls walking through the forest, concluding the tale with a moral, warning womenfolk and girls about the perils of being trustful of men; that men might well beguile them and take on false appearances with some perverse or nefarious intent. In symbolic terms, the passage of the girl into puberty (the commencement of her menstrual cycle and the suggestion of blood) and the dawning of sexual awareness were other (veiled) themes embodied in the whiteness of her skin and her hooded red cape.

The outcome for the preteen girl in Perrault’s version of the folk tale is tragic; at her grandmother’s house, the disguised wolf eats her when she climbs into her grandmother’s bed, and so the story ends. Other (and newer) versions of this tale present a more favourable and even empowering outcome for the girl who lives. Before briefly undertaking an analysis of a postmodern anti-fairy tale version of Little Red Riding Hood, as evidenced in the writings of Angela Carter, the English novelist, we need a brief definition of what an anti-fairy tale is. The contributor Wolfgang Mieder in The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales designates an anti-fairy tale as that which has a tragic rather than the normal (expected) happy ending, so characteristic of the fairy tale genre. Mieder reminds the reader that the most optimistic fairy tale often contains elements of the anti-fairy tale, also noting that:

[…] the term (anti-fairy tale) has also been used to refer to modern literary reworking of fairy tales that stress the more negative scenes or motifs, since they appear to be more realistic reflections of the problems of modern society.

In her 1979 collection The Bloody Chamber, Angela Carter presents three stories with the wolf as a central theme: The Werewolf, The Company of Wolves, and Wolf-Alice. Her story The Company of Wolves formed the foundation of the film director Neil Jordan’s 1984 fantasy horror movie of the same name. The three stories are well referenced in an article written by Bidisha on the British Library website, exploring gender and sexuality, fantasy and fairy tale, and identity. In The Bloody Chamber (which includes a story of that name and nine other tales), Carter weaves subversively dark and sensual forms of traditional fairy tales, such as Bluebeard, Beauty and the Beast, Puss in Boots, and Little Red Riding Hood— doing so in a richly romantic, gothic style.

The Werewolf is a version (in less than three pages) of Perrault’s Little Red Riding Hood, but with a twist. The child (heading to her grandmother’s house with oatcakes) is attacked by what appears to be a wolf. She hacks off one of its paws with her father’s hunting knife. The wolf flees, and she wraps the paw in the cloth containing the oatcakes. She continues to her grandmother’s house and finds her ill in bed. While taking the cloth (containing the oatcakes and paw) to wipe her grandmother’s brow, the ‘paw’ (now returned to its former form as a human hand) falls to the floor. The child recognises the freckled and age-worn hand—bearing a wedding band on the third finger and a wart on the index finger—as that of her grandmother, and then discovers she is missing her hand. With neighbours alerted by the child’s cries, the grandmother is forced from her house and stoned to death, leaving the child to inherit the house and eventually prosper.

Carter’s retelling combines the grandmother and wolf to form a werewolf, and presents a good, resourceful child, who (being a mountaineer’s child), is fearless. She triumphs over adversity—a strong, liberated female. Carter uses the theme of wolves in her last three stories to explore sexual and gender politics, societal violence, and the prospect of liberation.

Conclusion

This essay posed whether the anti-fairy tale is superior to the traditional archetype fairy tale, by focussing on the European tale Little Red Riding Hood. By briefly considering the conception of the fairy tale by Countess d’Aulnoy and the work of the conteuses, The Brothers Grimm, Perrault’s original tale, and the work of Angela Carter, known for her anti-fairy tales, it can be fairly concluded that neither is superior as a literary form to the other. The fairy tale classics remain protected as products of their time; the anti-fairy tale keeps its right to co-exist.

Bibliography

Artist Unknown, Angela Carter, Unknown, Photograph <https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/authors/4389/angela-carter>

———, Engraving of French author Charles Perrault (1628-1703), 1671, engraving, Palace of Versailles <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_Perrault02.jpg>

Ashley, Melissa, The Bee and the Orange Tree, Hardback Edition (Melbourne, Australia: Affirm Press, 2019) <https://affirmpress.com.au/publishing/the-bee-and-the-orange-tree/>

———, ‘The Bee and the Orange Tree’, The Bee and the Orange Tree <https://melissaashley.com.au/>

———, ‘The First Fairytales Were Feminist Critiques of Patriarchy. We Need to Revive Their Legacy | Melissa Ashley’, The Guardian, 2019 <http://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/nov/11/the-first-fairytales-were-feminist-critiques-of-patriarchy-we-need-to-revive-their-legacy>

Basan, Pierre-François, Portrait of Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville d’Aulnoy (Countess d’Aulnoy), 18th century, engraving, Palace of Versailles <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:D%27Aulnoy.jpg>

Bidisha, ‘Angela Carter’s Wolf Tales (“The Werewolf”, “The Company of Wolves” and “Wolf-Alice”)’, The British Library (The British Library, 2016) <https://www.bl.uk/20th-century-literature/articles/angela-carters-wolf-tales>

Biow, Hermann, The Brothers Grimm (Daguerreotype 1847), 1847, Photograph <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brothers_Grimm_Blow.jpg>

Carter, Angela, The Bloody Chamber (London: Vintage Books, 2006)

Haase, Donald, ed., ‘Anti-Fairy Tale’, in The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales: A-F, 3 vols (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008), p. 50

Jolles, André, Simple Forms: Legend, Saga, Myth, Riddle, Saying, Case, Memorabile, Fairytale, Joke. (Brooklyn, New York, United States: Verso, 2016)

Jordan, Neil, The Company of Wolves (ITC Entertainment, 1984) <https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0087075/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0>

Prawny, ‘Fairytale, Fairy Tale, Enchanted’, Pixabay, 2016 <https://pixabay.com/illustrations/fairytale-fairy-tale-enchanted-1735406/>

‘The Arthur Rackham Society’, The Arthur Rackham Society <http://arthur-rackham-society.org/>

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel, The Lord of the Rings, 1968 Single-Volume Edition (Canada: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1968)