Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic

In this essay, I explore how adoption of the graphic novel form by the American cartoonist Alison Bechdel for her 2006 autography Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic allowed her, I contend, to create a narrative with a deeper, more nuanced message than that possible in prose form alone.[1] Of the 240 pages comprising Bechdel’s graphic memoir, I have based my close analysis on pages 219 to 222, contextualising my findings within the broader text.

As the rear cover blurb to the graphic novel states, Fun Home is a memoir ‘marked by gothic twists, a family funeral home, sexual angst and great books.’ The reader is introduced to Alison and given access to memories from her childhood and young adult life in Pennsylvania, USA. In particular, we are shown the complex relationship with her father, Bruce Bechdel, an ‘obsessive restorer of the family’s Victorian home, funeral director, high school English teacher, icily distant parent and closeted homosexual, who […] is involved with his male students and a babysitter.’ The reference to “fun” in the novel’s title alludes to the family business; one might otherwise read this as Fun(eral) Home: A Family Tragicomic.

Fun Home combines a mix of ‘alternately heart-breaking and fiercely funny’ narrative, addressing dysfunctional family dynamics that embody the complex themes of emotional abuse, suicide, sexual orientation and gender roles in a graphic novel format. The reader may appreciate how Fun Home can, therefore, fulfil a central criterion for inclusion in Priestley’s Tales of the Unexpected, i.e., a desire for the publication to be “fuelled by dark and unconventional stories that twist the familiar into the uncanny,” as stated in the publication’s strapline. Rather than presenting a home that is nurturing and fun, I would suggest that Alison’s Fun Home might be considered unheimlich—a German word noted by Freud as the antonym of heimlich, or ‘homely’—therefore denoting ‘unhomeliness’. The reader is presented with a narrative that is interleaved with a sense of the uncanny—the psychological impression engendered by events that, rather than being mysterious alone, we perceive as being oddly familiar, and therefore unsettling. Expressed differently, the familiar is seen in an unexpected or out of context way that challenges our worldview, so destabilising it.

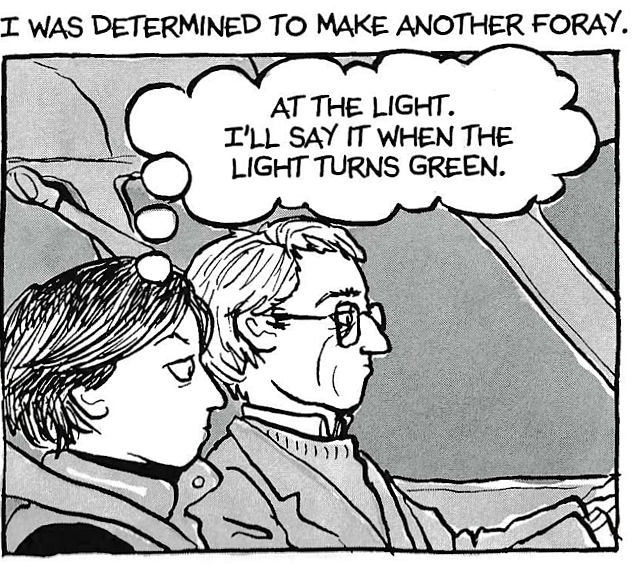

Alison Bechdel’s yearning for a closer relationship with her emotionally distant father takes on new significance and urgency when she comes out as homosexual in her late adolescence. At the bottom of page 219, Alison and her father agree to go, by car, to see a movie together. Alison intends to use their time in the car to broach the subject of both her sexuality and that of her father, i.e., their shared predilection, using the earlier gift of a book from him, with homosexual themes, as a way in.

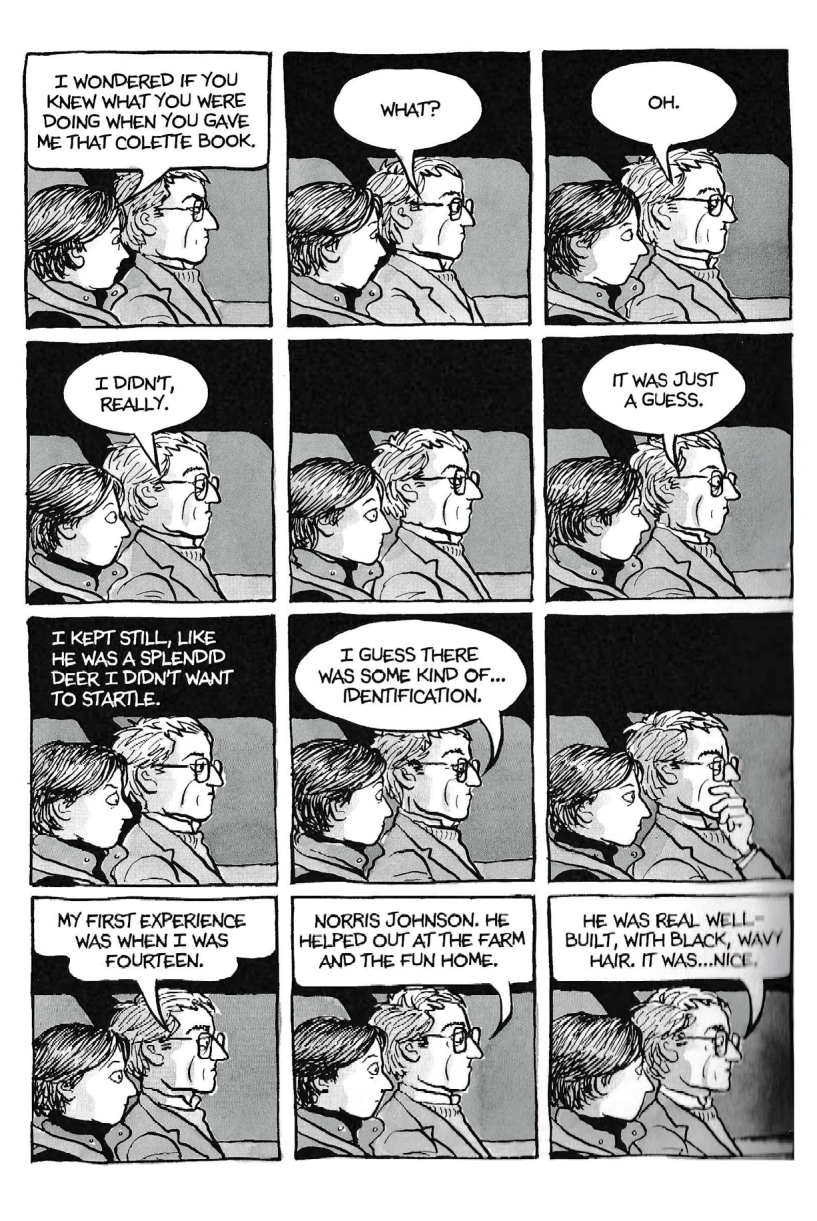

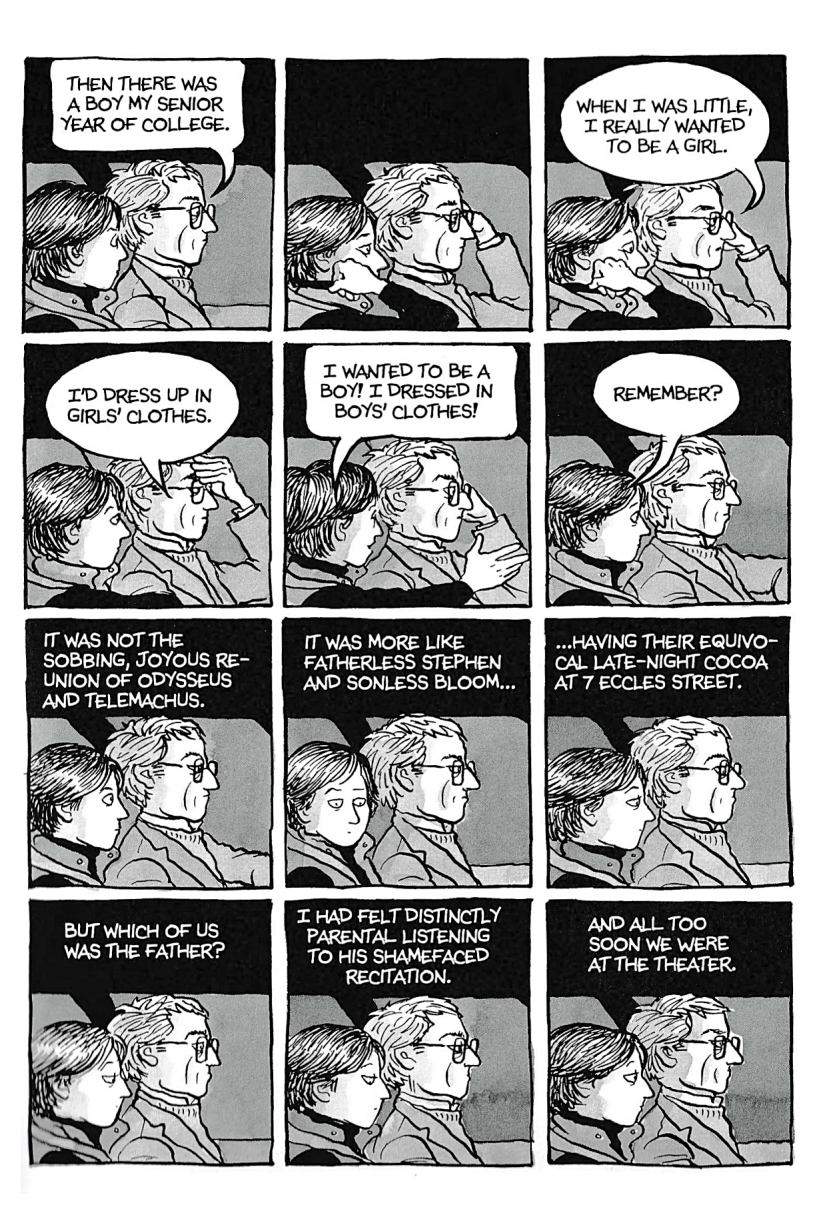

When one turns to pages 220 and 221 in the novel, Bechdel presents a spread of tightly packed image panels, incorporating framed boxes of equal size—twelve to each page, twenty-four in total. Although the presentation format is constant throughout—i.e., we see the side profile of Alison sat beside her father, with both facing to the right as they drive—Bechdel draws each panel frame afresh, either with or without text; a meticulous, labour-intensive approach that makes each frame within each panel unique, i.e., there are no simple cut-and-paste repeats. This process accommodates both the overall commonality of their shared experience travelling in the car together, with the uniqueness of each passing moment, i.e., the twenty-four patiently redrawn frames reminding us that no two moments in time can ever be the same; they might be similar, but not identical—as is also true of the unfolding individual thoughts and the conversation between Alison and her father.

The car sequence suggests a stifling, awkward tension between the two, evidenced, for example, in an internal reflection by Alison, in which we read, ‘I kept still, like he [her father] was a splendid deer I didn’t want to startle’ (Bechdel, p. 220). The near filmic quality produced by the frames reminded me, a little, of the effect achieved by use of the Dutch angle (or Dutch tilt) technique in film making and photography, where the tilting of the camera produces a viewpoint akin to the tilting of one’s head to the side, the object being to portray psychological tension and uneasiness. In the car scene, there is no visual tilt, but one senses the psychological tension and uneasiness, nonetheless. I suggest that in some subtle, visual way, Bechdel’s use of this tight, equal-sized, regimented block format provides a similar effect to that achieved by the use of the Dutch angle technique. It is of note that Bechdel’s stylistic choice for the car scene is not replicated elsewhere in Fun Home. Bechdel achieves the effect of making the conversation between Alison and her father appear stiff, faltering, and brief, albeit over (an agonising) two pages, accentuating the drawn-out dis-ease between them—all within a moving vehicle from which there is no immediate escape: a relatable experience for many of us. My reference shortly to comments by Monica Pearl about the car sequence lends weight to my observations above.

Further, absent in the car sequence is Bechdel’s use of visual and textual devices used elsewhere in her novel, e.g., writing outside of the frame panels, the bleeding of text or images to the page borders, and the occasional inclusion of amusing and informative intradiegetic or extradiegetic remarks in boxes, from which arrows point to the thing being highlighted. The result of Bechdel’s pared-back approach with the car sequence is to enhance the sense of constraint, of being boxed in.

There are eleven frames where no verbal conversation occurs at all. However—and this is where the use of images with or without textual aid can trump the use of a prose form alone—the awkward verbal silence stresses the non-verbal communication that is observed. At such times, Bechdel conveys emotion by changing her characters’ facial expressions, particularly those of Alison; this alone is a reason for Bechdel to have avoided the temptation of using a cut-and-paste approach for her images. I would contend that the skilled portrayal of a character’s emotions by a prose writer is well matched, if not surpassed at times, by the minimalist, immediately comprehensible pictorial portrayal of emotions possible in a well rendered graphic image, like those achieved in the car sequence in Bechdel’s graphic novel.

To reiterate my last points more concisely and eloquently, in his 2011 article, The Space Between: A Narrative Approach to Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, Robyn Warhol states that, ‘Fun Home shows how the addition of visual images to the verbal narration […] in autography can produce a depth-effect to characterisation that goes beyond what prose autobiography typically can achieve.’[2] I agree with Warhol’s assessment. As I do with the statement by Versaci on page 36 of his 2007 novel that, ‘while many prose memoirists address the complex nature of identity and the self, comic book memoirists can represent such complexity in ways that cannot be captured in words alone.’[3]

For example, besides the subtle changes to facial expression achieved by Bechdel, the reader is presented on seven occasions with Alison’s accompanying internal thoughts by use of the deliberate visual device of white text on a black background, which contrasts with the normal black text on a white background within speech bubbles seen during the verbal exchanges between Alison and her father. In her 2009 article, Graphic Language, in which she comments on the car sequence, Monica Pearl refers to this process by Bechdel as a way

[….] to set off both the stilted conversation and the etiolated and resigned thought process at this loaded moment in the text, drawn in white against the black background. The white writing against a black background also creates the impression of a photographic negative, suggesting the momentary reversed dynamic between parent and child (p. 289).[4]

One can see an example of that ‘reversed dynamic’ with Alison’s internalised statement, ‘I had felt distinctly parental listening to his [her father’s] shamefaced recitation’ (Bechdel, p. 221). Bechdel’s heavier use of pure black in the car sequence, against which are pitched Alison’s internalised thoughts, is in stark contrast to the lighter tones, or colouration, of the author’s drawings elsewhere in Fun Home, creating a brooding, darker feel in the car sequence and increasing the tension between daughter and father. There is constant shifting between one thing and another. Pearl alludes to this duality of things in Fun House in the introduction to her article, stating that

Fun Home […] is a book of paradoxes and juxtapositions—and not only those of visual and written text […] We learn quickly that home is no home, and fun is not really fun. […] Other labels suggest but do not fully reveal or suggest one thing but mean another. The book is a representation of, and investigation into, the paradoxes of surface and substance.[5]

Pearl identifies a key characteristic of Bechdel’s use of the graphic narrative form: it allows the author to provide the reader with various levels by which they may understand her complex story—the immediacy of the surface message, plus all that lies beneath, ready to be discovered.

It seems wholly appropriate that Bechdel’s graphic novel should have been visually re-imagined as a five times Tony Awards winning Broadway musical called, as one might expect, Fun Home.[6] The ‘telephone wire’ car journey song from the musical, playable on YouTube from Fun Home Lyrics, accentuates with painful clarity the words said, and unsaid, between Alison and her father. It is conjointly both comical and painful to listen to, and provides additional appreciation, and understanding, of the car journey graphics and text in Bechdel’s novel and of the dysfunctional relationship between father and daughter.

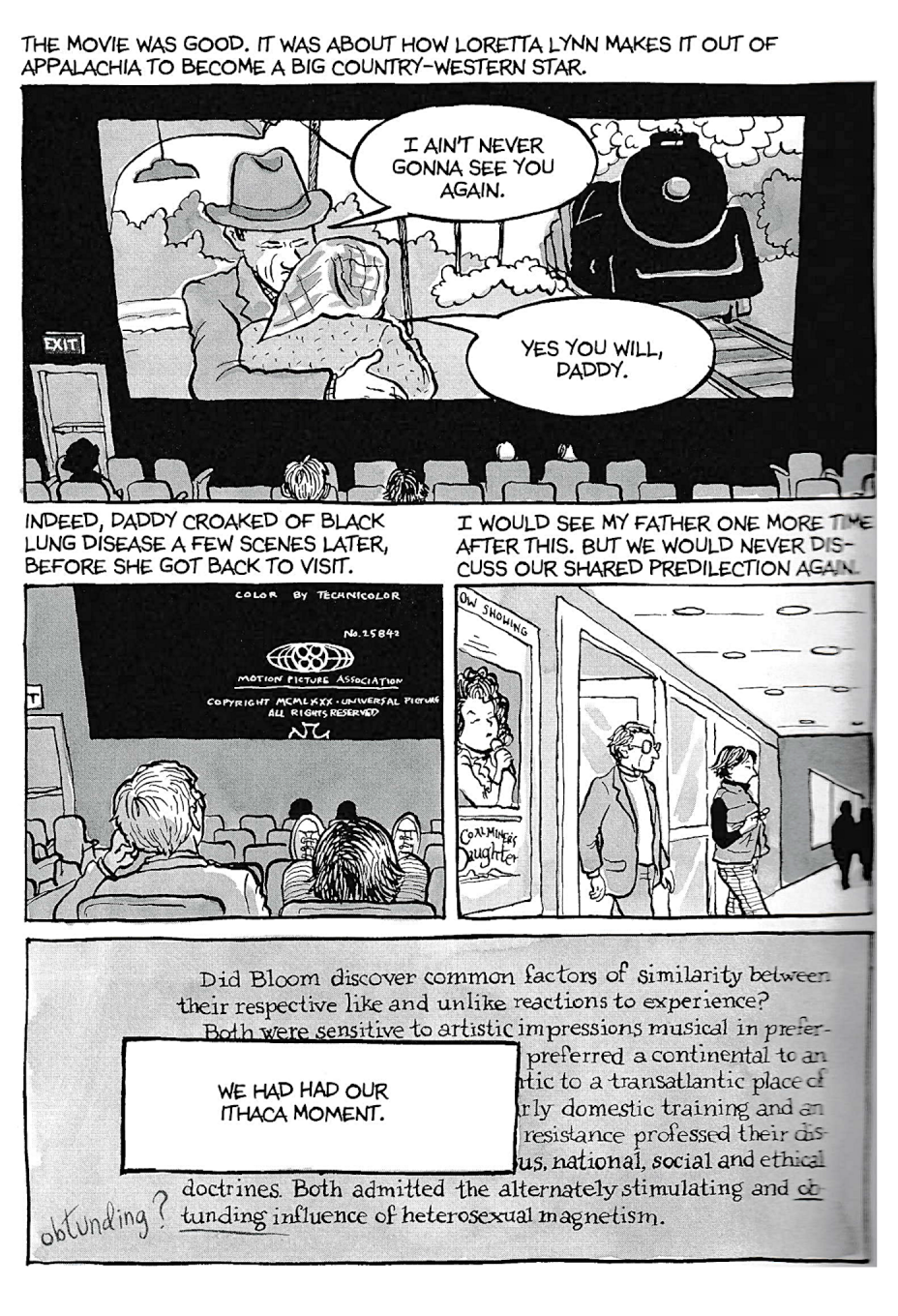

That dysfunctional relationship remains until the end. On a car journey in which both Alison and her father are gifted with ample opportunity to bridge the gulf between them, neither finds themselves capable of doing so. In silence, they reach their destination and, still sitting side by side, watch the movie together: Coal Miner’s Daughter, the biographical musical film that follows the early years and rise to fame of the country music singer, Loretta Lynn. That Lynn also had a challenging family upbringing was not lost on me.

A closing scene in the movie panel on page 222 of Bechdel’s novel shows Lynn’s father saying to his daughter, ‘I ain’t never gonna see you again,’ with Lynn replying, ‘Yes you will, daddy.’ Lynn does not, for her father dies of black lung disease before she next sees him. One wonders at the relevance of this scene inclusion by Bechdel, but perhaps it was intended as nothing more than a simple foreshadowing of what was to transpire in Alison’s life for, on the same page, as Alison leaves the movie theatre with her father we read, above the image frame, the words, ‘I would see my father one more time after this. But we would never discuss our shared predilection again.’ This is the point nearing the end of Alison’s relationship with her father; a vehicle would soon strike him, and he would die from his injuries—an act of apparent suicide. Like Lynn, Alison does not get to see her father alive again.

The outing to the movie theatre ends on page 222, with a panel suggesting more than a surface message alone, as is so often the case in Fun Home. Superimposed over some text from the book Ulysses by James Joyce is a text box with this thought from Alison: ‘We had had our Ithaca moment.’ A simple six-word statement. It is a further example of Bechdel’s numerous references throughout her novel to classic texts, closing this page with an explicit reference to Joyce. The chapter in question in Joyce’s novel follows Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom to the latter’s house, where they have a conversation, before Bloom goes to sleep. Although the penultimate chapter in Joyce’s novel, ‘Ithaca’ is sometimes seen as the actual end of the story: a ‘homecoming’ that completes Bloom’s day-long journey around Dublin, his home city. Bechdel, in her novel, appears to be paralleling her closing relationship with her father with that of Dedalus and Bloom, but what more significance might there be to this beyond one of catharsis, and beyond continuing the tradition of intertextual framing with canonical works, such as that by Joyce? What is Alison’s ‘homecoming’? I would be keen to hear your thoughts in the comments. For those wishing a detailed analysis of intertextuality in Bechdel’s Fun Home, I would recommend reading Caitlin Walker’s academic essay for the Scarlet Review (Rutgers University, Camden, New Jersey, USA) titled Intertextuality in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home.[7]

In closing, I would note that the connection to Ulysses may well be lost on anyone who had not read Joyce’s modernist novel, but that having not made such a link would not detract from the power of Bechdel’s message throughout—or of the stylistic choices and nuances achieved by her use of a graphic memoir format. The ‘Ithaca’ moment is yet another example of the multi-layered, textured approach accomplished by Bechdel. A simple six-word statement, but with a depth of meaning to be discovered—as with the book in toto.

Order details

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel. My edition published by Jonathan Cape, September 14, 2006. 240 pages, paperback. Dimension: 227 x 148 x 15 mm. Weight: 429g. Language: English. ISBN 9780224080514. RRP £16.99 ($18.99).

Literary awards

Stonewall Book Award for Non-Fiction (2007); Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Memoir/Biography (2007); Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards for Best Reality-Based Work (2007); The Publishing Triangle Award for The Judy Grahn Award for Lesbian Nonfiction (2007).

Works Cited

[1] Alison Bechdel, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (London: Jonathan Cape, 2006).

[2] Robyn Warhol and Robyn Warhol-Down, ‘The Space Between: A Narrative Approach to Alison Bechdel’s “Fun Home”’, College Literature, 38.3 (2011), 1–20 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/41302870> [accessed 28 October 2022].

[3] Rocco Versaci, This Book Contains Graphic Language: Comics as Literature (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2007).

[4] Monica B. Pearl, ‘Graphic Language: Redrawing the Family (Romance) in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home’, Prose Studies, 30.3 (2009), 286–304 <https://doi.org/10.1080/01440350802704853>.

[5] Pearl.

[6] Fun Home: Telephone Wire, dir. by Fun Home Lyrics, 2016 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N_US4P9zPQQ> [accessed 3 November 2022].

[7] Caitlin Walker, ‘Intertextuality in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home’, The Scarlet Review, 2018 <https://scarletreview.camden.rutgers.edu/archive/2018edition/funhome.html> [accessed 11 August 2025].